Remembering the Drummer’s Finest Hours

“Why are you always smiling Ginger?”

“Because I’m happy!”

It was 1963 and the flame haired drummer sitting at the back of the crowded club room was having a ball. He was clearly in seventh heaven as he powered up a lively R&B group jamming away at the 1963 Richmond Jazz & Blues Festival.

So was the audience in heaven, blown away by the wild eyed young man rapidly achieving fame as Peter ‘Ginger’ Baker. Not so much a percussionist as a concussionist, he knocked out fans and fellow musician alike with an ear blasting, passionate performance on a drum kit that he would later confess he’d made himself.

Along with those drums, Ginger was a self made man. He fought for everything he would achieve in life. Often he lost his battles, but there was something Napoleonic and inspirational about his heroic struggles. Whether it was forming a super group, driving across the Sahara desert, setting up a recording studio in Africa or trying to establish polo grounds on foreign fields, Mr. Baker was never afraid to take up a challenge.

In the wake of his sad death aged 80 on October 6th, 2019 much has been made of his fiery temperament, angry outbursts and catastrophic exploits. But there was always a warmer, human side to Mr. Baker. He had a strong sense of humour and could be surprisingly self effacing. In his cups he was generous, friendly and loyal. If he seemed steeped in anger in later years, when beset with ill-health, then much of that anger was directed at himself.

BACK TO THE FUTURE

It was Bill Carey, an enthusiastic Canadian compere who presided over the bill and greeted Ginger at the Jazz festival that afternoon back in ’63, an event that also featured an early appearance by the Rolling Stones. R&B had become an overnight force to be reckoned with and was sweeping Trad Jazz off the music press front pages.

Ginger had clearly found a home with musicians ready to play the kind of electric blues pioneered by Muddy Waters, rather than recycle 1940s bebop.

Of course the drummer loved modern jazz and his earliest heroes were Max Roach, Art Blakey and Phil Seamen, the British drummer who became his friend and mentor. He played trad style with the Terry Lightfoot band but also sat in at Ronnie Scott’s Club. Older musicians generally regarded him as too loud, aggressive and untamed. These were all the qualities that made him so exciting to see in action.

When Ginger played in that stuffy back room at the Richmond Athletic Ground on a hot afternoon on August 11, 1963 with a group led by Alexis Korner and Cyril Davies (I do believe), I stood as close to the kit as possible. We all watched Ginger attacking his drums with tremendous speed and violence, hair and limbs flying. This wasn’t just about keeping time. Ginger’s playing was all part of the musical experience, as important as the riffs from the guitarist and the wail of the harmonica.

It was a style he would refine with The Graham Bond Organization, often seen performing at The Black Prince, Bexley jazz club. I reviewed the band with Graham, Ginger, Jack Bruce and Dick Heckstall Smith (known as Hacksaw Smith) for the Kentish Times. As soon as I joined Melody Maker in October1964 I suggested we should interview Ginger for a special feature. Editor Jack Hutton cheerfully agreed. Ginger was making waves and the MM was keen to find out more about this rising star of the R&B world. Charlie Watts of the Stones was raving about him, so that was an added incentive.

MEETING THE MONSTER

We met for the first time in a pub off Leicester Square and he greeted me with a smile and an apology as he rushed to the bar. He was sorry to be late. He’d just been to the dentist and his jaw was aching. (Years later, he laughed when I mentioned that Sixties’ dental appointment. He confessed he’d actually been to see somebody else…).

The MM story was headlined: ‘Ginger Baker, one of Britain’s Great drummers tells us: ‘I Know I’m A Bit Of a Monster.’

It went on: ‘They call him the Thunder Machine. But Ginger Baker is no machine. He is an emotional 25 year old who plays drums the way he feels they ought to be played. Despite criticism, he has become the idol of Britain’s beat drummers and still earned the respect of such jazzmen as Phil Seamen. More than a select few are beginning realise he is one of the great drummers’.

Ginger told how he used to freelance at Ronnie Scott’s Club. ‘I was rather controversial. I was always ‘too loud!’ But I don’t like these guys that play like a metronome. I know I’m a bit of a monster. I have always been big headed but people whose playing I liked, always liked mine and that kept me going. Ronnie changed his policy and I lost any work I ever had. After a while I joined Alexis Korner, mainly through a nice gesture by Charlie Watts who is a nice guy and a very good player, although he doesn’t seem to think so. Since then I’ve had the best time ever and Alexis helped me become a non-monster.

“When I joined Graham Bond we found the going very hard but it has paid off. I’m really enjoying myself. We’ve had our rows but the music always holds us together.”

“When I joined Graham Bond we found the going very hard but it has paid off. I’m really enjoying myself. We’ve had our rows but the music always holds us together.”

One of the most exhilarating aspects of Ginger’s drumming, especially during solos like Oh Baby with the Bond Organization, and later on his showcase number Toad with Cream, was his ability to orchestrate a roar of climactic rolls on his snare drum, tom toms and double bass drums. How did he do it?

“I can play as fast with the right foot as I can with my right hand,” he explained. “To get four different things going at once, you have got to remove a mental barrier…get the left hand going and forget about it. Independence is about splitting the brain into four.” He demonstrated this idea by drumming with his hands on a table top and with a box of matches. Wish they’d invented the cassette recorder in 1964.

After that first meeting, Ginger was always willing to chat and remained friendly and cheerful over the years, despite the occasional warning grumble. I’d go and see him play whenever possible in TV studios, at rehearsals, club gigs, concerts and festivals. Often he’d be laughing while playing at his best, satisfied when it was all coming together and working with musicians he most admired.

Even so, it was touch and go at a Chuck Berry concert at the Gaumont Lewisham one night in 1965 when the Organization was supporting the equally temperamental guitarist. Promoter Robert Stigwood had invited me backstage to get an eyewitness view of proceedings.

Just as ‘Ginge’ was about to unleash his big solo of the night, the bass drum pedal strap broke. ‘Oh FUCK!’ he shouted in a rage, picking up the offending pedal and smashing it to bits on the stage floor. It seemed sensible to avoid any kind of conversation later in the dressing room.

But Mr. Stigwood politely asked me to write sleeve notes for the debut Graham Bond album The Sound Of 65 which I was pleased to provide.

The LP was adorned with a bright red cover painting by Ginger, in the style of Jackson Pollock. I delivered my typewritten notes to Robert at his office, and he fished around to pay for them with a crumpled ten shilling note. (All of 50p).

In July 1966 Ginger phoned and excitedly told me that he’d left Graham and was forming a group with himself, Eric Clapton and Jack Bruce. We ran a story in the MM but there wasn’t much space for more than a couple of paragraphs. It should have been front page news. Ginger was not impressed. Nor were the managers of all the groups who believed Eric, Jack and Ginger were contracted to play with THEM. Heated denials followed. Clapton was supposed to be with John Mayall, Bruce with Manfred Mann and Baker was still a Bondsman although soon to be replaced by Jon Hiseman.

However, the story was confirmed the following week and I was invited to see Cream rehearsing at a church hall in North London in July 1966. They were readying for their debut at the Sixth National Jazz & Blues Festival.

SWEET ’N’ SOUR ROCK & ROLL

Eric was nervous about the prospect and insisted that Cream was definitely NOT going to be a jazz group. He called their music Sweet and Sour Rock’n’Roll. However, I suspected Ginger and Jack had other ideas. Eventually, with Pete Brown co-writing clever lyrics, a strange but successful musical brew would emerge.

The nascent group gathered in front of an audience of Brownies and a caretaker sweeping the floor, armed with minimal equipment. The boys stood around in a sea of cigarette ends and prepared to run through a few numbers. Ginger, sporting a villainous-looking beard, crouched over his drum stool set in its lowest possible position and a ride cymbal sloping upwards like a 1-in-2 hill. Wielding a pair of enormous sticks he told me: ‘Phil Seamen calls ’em Irish navvy poles’. He suggested the band play their latest ‘comedy number.’ This proved to be a jug band tune called Take Your Finger Off It.

Eric looked at Jack and grinned: ‘You mucked up the end.’ ‘Yes, I did, didn’t I,’ said Jack coolly. A worried Robert whispered in my ear ‘Are they any good?’ I was surprised but flattered to be asked.

Eric looked at Jack and grinned: ‘You mucked up the end.’ ‘Yes, I did, didn’t I,’ said Jack coolly. A worried Robert whispered in my ear ‘Are they any good?’ I was surprised but flattered to be asked.

I assured the manager they were…well…great! In fact I called them ‘a super group’. And they sure were, even when stepping out to play small pub gigs like Klooks Kleek, in West Hampstead. It was more enjoyable than seeing them at the Windsor jazz festival when it poured with rain.

Then came the albums, Fresh Cream and Disraeli Gears and hit songs like White Room, Tales of Brave Ulysses and Sunshine of Your Love, the classic rock anthem when the drummer set up his trade mark Apache style rhythm.

Cream’s albums were packed with great performances, yet it was always my personal feeling that Ginger’s drums sounded at their best on the first Graham Bond album, when he energised arrangements like Hoochie Coochie Man, Spanish Blues and Wade In The Water.

Certainly the latter instrumental number impressed Bill Bruford, the Yes drummer who wrote in a letter of praise to the MM. Indeed, Ginger was inspiring a whole a new generation of drummers. John Bonham of Led Zeppelin was a fan and every beat group in the country now gave solo space for drummers to show off their skills. Ginger had joined the ranks of Keith Moon and Mitch Mitchell, each with their own distinctive style and vibrant personality.

DINNER WITH THE BAKERS

Ginger Baker conquered the stage at the Saville Theatre and the Royal Albert Hall in London and on treks around Europe and the United States whenever he launched into full scale assaults on a now vastly expanded drum kit with double bass drums. Two years of hits and sell out tours had passed when I was invited to 28-year-old Ginger’s home in Harrow for dinner with his wife Liz and two children Ginette ‘Nettie’ (then aged 7) and Leda (aged 5 months), in August 1968.

Clad in a black leather jacket, he drove me from the MM’s Fleet Street office to Harrow in his brand new Jensen FF. ‘It’s the safest car in the world’ Ginger assured me, as we hurtled down Park Lane. ‘I got it for £5,000. It’s the best car I’ve ever had.’

Since Cream had recently returned from America and Eric had announced that they were breaking up, rumours have been rife about Ginger’s future. It was expected he would eventually form his own band. “It depends how we feel” he explained as we settled in his lounge at home. “Cream can’t go on forever, and I’m going to retire in three years time anyway. I think Eric wants to move on to do more things musically than with the Cream, and rightly so”.

I wondered if Ginger liked his ‘live’ version of Toad on the Wheels of Fire album. “There are some good things on it. A couple of impossibles and a couple of things that didn’t come off. Half of it didn’t come off. But Phil Seamen heard it, and said half of it DID come off.”

Did he ever panic if things started going wrong in a solo? “No. But you get some brick walls floating about. If you worry about them, then you’re in trouble. Most people play by thinking all the time. Not many just turn on.

“I don’t know what will happen now, but I think it would be insane not to carry on for another nine months with Cream. The potential, especially Eric’s, is ridiculous. There are more things that should be played and written. But apart from these hang-ups, I feel very happy. I’ve been playing for 13 years and now I’ve got some security for my wife and kids, and that’s the important thing.”

As the dinner plates were cleared away Ginger added: “I like people and I like to play music they like. It’s nice to hear their applause.”

“Well you’re just an ego-maniac,” said Liz, keeping one eye on the Baker boots. “But I don’t think you’re weird.”

It was always a pleasure to join the family for dinner and on another evening at their home, Ginger decided to regale guests with a barrage of beats on his collection of African drums. ‘Do you have to play so loudly? Three of us are trying to get to sleep you know!’ It was daughter Nettie peering down the stairs in her nightdress at her father who was wielding a massive pair of wooden clubs, while hammering out primitive rhythms in the hall.

Cream played their last show at the Royal Hall in November 1968 and Ginger was filmed in action for BBC TV by director Tony Palmer. Baker would later go on to play in Blind Faith with old mates Eric Clapton and Steve Winwood. They recorded one album and performed at their laid back 1969 Hyde Park, London free concert, before splitting following a gruelling American tour.

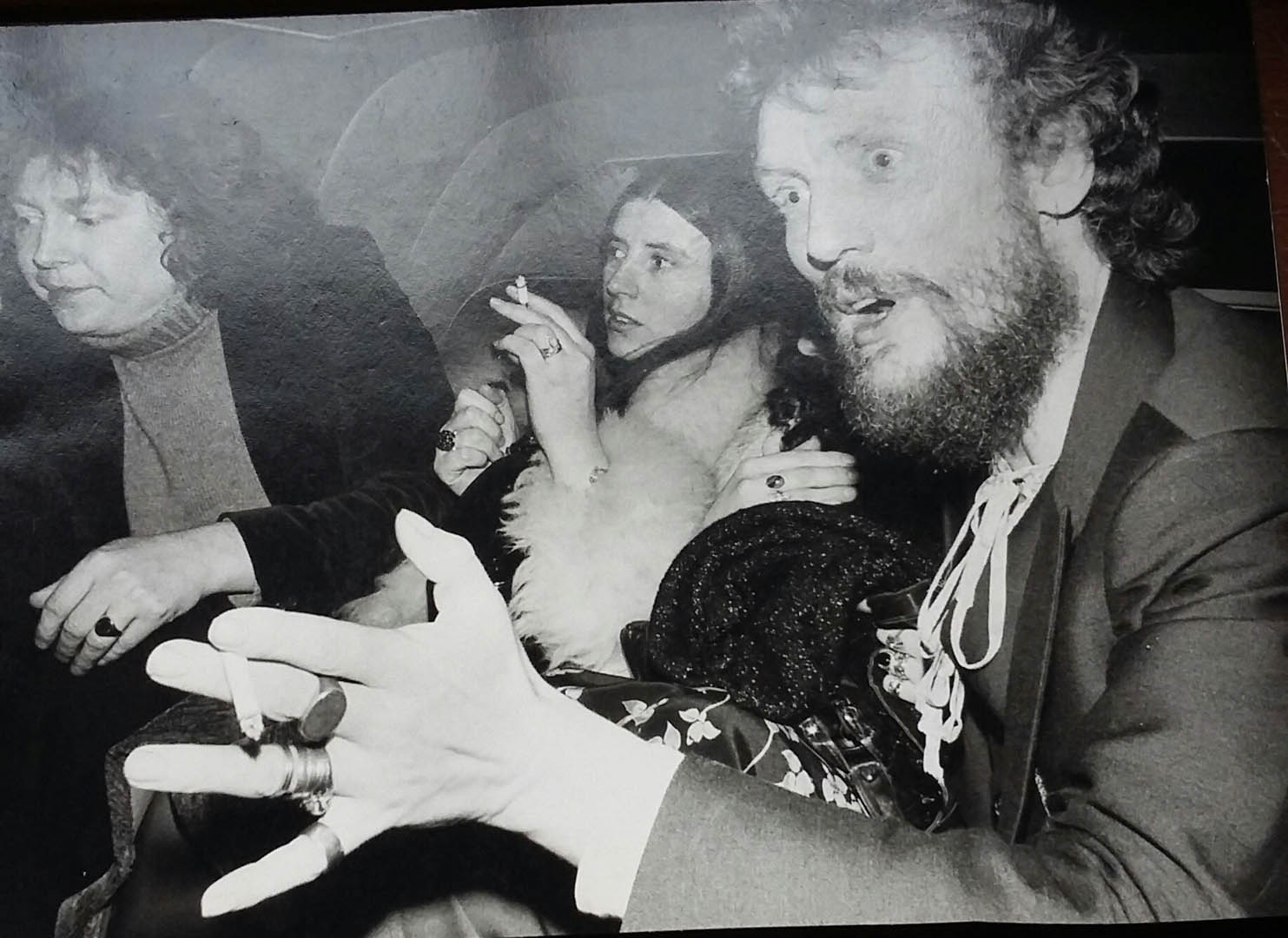

Ginger Baker’s Airforce took off in 1970 and the leader recruited Graham Bond and Phil Seamen amongst an all star cast that roamed the country creating musical havoc. I saw them at a memorable concert in Birmingham, when third drummer Alan White complained that Phil had pinched his drum sticks, just before the show. Airforce was soon grounded but by 1975 Ginger had teamed up with guitarist Adrian Gurvitz in the Baker Gurvitz Army. My wife Marilyne and I were invited to see them on an exciting trip to Paris. I remember Ginger exchanging insults with a lone American tourist in the lobby of the George V hotel on our arrival. Somehow they didn’t see eye to eye over matters of dress code. Undaunted we explored the city in a limo and saw the evening show in front of an excitable French teenaged audience.

Marilyne was renewing her acquaintance with Ginger, who she first met aged eight, when he visited her parents’ home in St. Paul’s Cray, seeking out her brother John, a brilliant 14 year old clarinettist he’d enlisted to play in Ginger’s trad jazz band. She remembered him arriving clad in a bright green jacket and jeans and sporting long red hair that created a sensation back in 1955.

In 1971 Ginger was a very welcome guest at our wedding and he even played drums at the church hall reception. The ad hoc band included Greg Lake, Carl Palmer, Keith Emerson and Peter Frampton. (Sadly they wouldn’t let another guest Marc Bolan sit in and sing. I don’t think they knew the chords to Ride A White Swan.)

CREAM REUNITED

The drums and the years rolled by. One day I got a surprise call at home in 1981 (or thereabouts) from Ginger saying he was planning to leave the country and wanted to say goodbye. I met him at Robert Stigwood’s Mayfair office where he picked up a large wad of cash due in royalties, which he waved about as we walked down the street to find his car. We drove out into the country to inspect his polo ponies and talk about his new life in Italy where he’d relinquish drumming and take up olive growing instead.

It was one of many adventures he had embarked on over the years, including the ill fated African recording studio and subsequent relocation to America where he volunteered as a fireman. Sometimes Ginger would phone long distance late at night to pour out his troubles and reminisce.

It was one of many adventures he had embarked on over the years, including the ill fated African recording studio and subsequent relocation to America where he volunteered as a fireman. Sometimes Ginger would phone long distance late at night to pour out his troubles and reminisce.

We met up again for the long awaited 2005 Cream reunion in London and New York, and it was truly great to see him playing at his best with Eric and Jack, one more time. They were greeted as heroes at the Royal Albert Hall and Madison Square Garden. They should have gone on a massive world tour. But with tension in the ranks resurfacing and Eric keen to call a halt, alas it was not to be.

Peter ‘Ginger’ Baker appeared on stage for one of his last major appearances, at Shepherd’s Bush Empire on October 25, 2016, for the tribute concert to Jack Bruce, who had died in 2014. Ginger had been playing with his Jazz Confusion group on returning to England from South Africa, where life had become even more confused. In the meantime he’d published a revealing and sometimes shocking autobiography Hellraiser in 2009 co-written with Nettie, who has since written two volumes of her best selling Tales Of A Rock Star’s Daughter. Ginger also starred in the award winning documentary movie Beware Of Mr. Baker (2012) shot by intrepid director Jay Bulger who received a whack on the nose for his troubles.

He may not have been in the best of health, was wracked by ‘constant pain’ as he told me at a final interview, but remained determined to get back behind his drum kit and play, whenever possible. “It’s what the public like to see me do. And I don’t ever want to let them down.” CHRIS WELCH